As sunshine peeked through the window, our yoga instructor began to talk about Seasonal Affective Disorder. I mouthed, “Political Affective Disorder” to my husband on the adjoining mat. He raised an answering eyebrow. The symptoms are similar: anxiety, lack of focus, feeling disheartened and deflated. It is something we’ve both experienced this year.

As we near the end of the year, I begin my annual taking stock and realize that this has not been a normal year. I am a goal setter; books read, blogs written, museums visited. You name it, I count it. This year I’ve given myself permission to lighten up. My five books a month fell to four. My blog frequency dropped. The gap of course has been filled with monitoring our political space, fearful that I might miss something that threatens life as we know it. This has taken a toll on my book reading and altered its nature.

Now normally almost half of my reading is non-fiction. That requires a level of attention and focus that I just didn’t have this year. Not only was I reading more fiction, but it had to immediately grip me. I was too easily distracted. More books lie abandoned for a failure to immediately engage. It is probably not their fault, more likely my diminished attention span. On the plus side, the books that survived my engagement test have often been extraordinary. I’ve long since abandoned reporting on a list of favorite books confined to a designated number, instead I will tell you over several posts, some of the standouts that share common themes or approaches. The ones in this post all seemed to serve some purpose for me in either finding calm or understanding the world around me.

Quiet Books With Depth

Quiet Books With Depth

I began the year by discovering the author Amor Towles, author of A Gentleman in Moscow. Trying to describe this book often fails to capture its extraordinary nature. A man is confined by house arrest to a hotel for the duration of his life. What dramatic possibilities does that permit? Well at least two and those prove to be rich and promising. We explore his character as he deals with these restrictions while attempting to have purpose and meaning in his constricted life. The fact that he is a witty and thoughtful character enriches this dimension. And remember he is housed in a hotel, and not just any hotel, the famed Metropol, with its regular cast as well as a constantly changing one. The world comes to him. A third dimension is added through the time period and location, beginning in Russia in 1922, it spans a period of thirty years. Having loved this book, I quickly sought others by this author and discovered Rules of Civility, a novel set in New York City in 1938. This rich novel explores the movement of a young woman into high society, despite more humble roots. Both novels present witty and well-developed characters, but of the two I must confess a preference for A Gentleman in Moscow with its more restricted circumstances, allowing a deeper dive into one character with less distraction. For me there was also significance in considering how we find meaning in life even when it has aspects at which we chaff.

I began the year by discovering the author Amor Towles, author of A Gentleman in Moscow. Trying to describe this book often fails to capture its extraordinary nature. A man is confined by house arrest to a hotel for the duration of his life. What dramatic possibilities does that permit? Well at least two and those prove to be rich and promising. We explore his character as he deals with these restrictions while attempting to have purpose and meaning in his constricted life. The fact that he is a witty and thoughtful character enriches this dimension. And remember he is housed in a hotel, and not just any hotel, the famed Metropol, with its regular cast as well as a constantly changing one. The world comes to him. A third dimension is added through the time period and location, beginning in Russia in 1922, it spans a period of thirty years. Having loved this book, I quickly sought others by this author and discovered Rules of Civility, a novel set in New York City in 1938. This rich novel explores the movement of a young woman into high society, despite more humble roots. Both novels present witty and well-developed characters, but of the two I must confess a preference for A Gentleman in Moscow with its more restricted circumstances, allowing a deeper dive into one character with less distraction. For me there was also significance in considering how we find meaning in life even when it has aspects at which we chaff. I then moved on to a NY based novel, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney. This too is a book that doesn’t lend itself to a quick snapshot. It begins with an 85-year-old woman who is on her way to a party, working her way through New York City on foot. It is another character study into a strong character with wit. Turns out Lillian Boxfish is based on the real-life character of Margaret Fishback, one of the highest paid female copywriters of the 1930s and known for her witty poetry and ad copy. The city of New York is also a central character viewed through a time dimension spanning from the 1920s to 1985. Just as A Gentleman in Moscow, much of it takes place in the head of the central character, a quieter kind of novel offering calm in a time of chaos.

I then moved on to a NY based novel, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney. This too is a book that doesn’t lend itself to a quick snapshot. It begins with an 85-year-old woman who is on her way to a party, working her way through New York City on foot. It is another character study into a strong character with wit. Turns out Lillian Boxfish is based on the real-life character of Margaret Fishback, one of the highest paid female copywriters of the 1930s and known for her witty poetry and ad copy. The city of New York is also a central character viewed through a time dimension spanning from the 1920s to 1985. Just as A Gentleman in Moscow, much of it takes place in the head of the central character, a quieter kind of novel offering calm in a time of chaos. The Immigrant Experience

The Immigrant ExperienceMany of the books I read offered an education in the immigrant experience, often the limited choices that undocumented immigrants face and what that may mean for their American-born children. Two books in particular explored this theme: The Leavers by Lisa Ko and Lucky Boy by Shanthi Sekaran. The Leavers is told through two voices, the mother, an undocumented Chinese immigrant, and her son, abandoned at age eleven without word upon his mother's deportation. He is adopted by well-meaning affluent parents, but remembers his former life and community, uncertain of his place within the world and his personal identity. Always lurking is the question of what happened to his mother, a mystery he ultimately solves.

Lucky Boy deals with the story of an undocumented Mexican immigrant who becomes pregnant on her way to America. She raises her child in his first year or two, a devoted mother, until she too is sent to a deportation center. Her child is given to foster parents, an Indian couple who loves him deeply, sympathetic people on both sides of this equation. Unable to claim her son, his mother is faced with a system which would readily remove her child if she doesn’t step outside of the rules. This was a side of immigration that was new to me and very disturbing. While told through fiction, it was true to the actual experience. There is a disconnect between federal immigration and the state child welfare system, with the latter often treating the child as if s/he has been abandoned when the parent is seized by ICE and housed at a deportation center. Often that is due to a lack of communication between the two systems.

Lucky Boy deals with the story of an undocumented Mexican immigrant who becomes pregnant on her way to America. She raises her child in his first year or two, a devoted mother, until she too is sent to a deportation center. Her child is given to foster parents, an Indian couple who loves him deeply, sympathetic people on both sides of this equation. Unable to claim her son, his mother is faced with a system which would readily remove her child if she doesn’t step outside of the rules. This was a side of immigration that was new to me and very disturbing. While told through fiction, it was true to the actual experience. There is a disconnect between federal immigration and the state child welfare system, with the latter often treating the child as if s/he has been abandoned when the parent is seized by ICE and housed at a deportation center. Often that is due to a lack of communication between the two systems. A non-fiction essay, Tell Me How it Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions by Valerie Luisella also offered a perspective on immigration with which I was unfamiliar, a glimpse into the experience of children immigrating from South America. The author volunteers as an interpreter for undocumented children who often flee alone to the United States. Safety from gangs is often an impetus, an issue in which the United States bears some complicity as the gangs arose in Los Angeles in response to Mexican gangs. Deportation of the gang members just served to spread the poison to a country which lacked the resources to hold them in check. The book is more about questions than answers. The children are asked to complete a questionnaire for information that is used by attorneys to explore avenues to keep them in the US. Luisella uses this questionnaire as the vehicle to tell the stories of the children.

A non-fiction essay, Tell Me How it Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions by Valerie Luisella also offered a perspective on immigration with which I was unfamiliar, a glimpse into the experience of children immigrating from South America. The author volunteers as an interpreter for undocumented children who often flee alone to the United States. Safety from gangs is often an impetus, an issue in which the United States bears some complicity as the gangs arose in Los Angeles in response to Mexican gangs. Deportation of the gang members just served to spread the poison to a country which lacked the resources to hold them in check. The book is more about questions than answers. The children are asked to complete a questionnaire for information that is used by attorneys to explore avenues to keep them in the US. Luisella uses this questionnaire as the vehicle to tell the stories of the children.

Scapegoating the "Other"

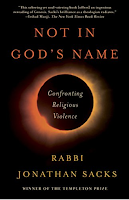

Much of my reading seems to have focused on trying to make sense of our world, so divided between us and them. To this end, I found a work by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks to be especially meaningful. In his book Not in God’s Name, Sacks focuses on the human tendency to turn on those we perceive as "other." He attributes it to our search for identity and for those who we identify as our tribe. Inclusiveness and exclusion go hand in hand. If we have identity, "us", we also see its inverse, "them". When our world fractures, we fall into dualism. Dualism is when we attribute evil to an outside force, simplifying the world into good and bad, us and them. Scapegoats are targeted and we tighten our group bonds by attacking the "other.” Sacks examines this concept through the lens of sibling rivalry as addressed in the Bible. Moving from Cain and Abel to Jacob and Esau to Joseph and his brothers, Sacks shows the evolution by example of how we are to resolve these differences. Ultimately, he finds the answer in role reversal, stepping into the “other’s” shoes. You can read a more extensive review I have written here.

Until beginning this post, I must confess that I hadn't realized the role that reading has played for me in making sense of this disturbing time. It has in fact served to deepen my understanding and helped me to find a place of calm from which to face this very uncertain world.